- Home

- Smita Bhattacharya

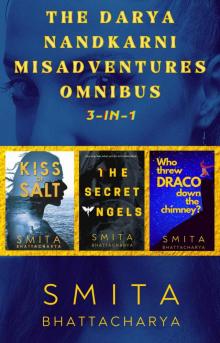

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3 Page 6

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3 Read online

Page 6

Darya shuddered now as she remembered how coolly her mother had said this. As if Aunt Farideh had gone from being a living person to a statistic, a picture on the wall with an incredible back story.

Her uncle looked for two years. Whenever a woman's body was found somewhere in Goa—a skeleton, a few bones in a hotel room or buried in the sand, a floating cadaver in the sea as it happened sometimes to a poor soul—he began his wild inquiries again. ‘Was it her? Was it a twenty-six-year-old, thin, white-complexioned, long brown-haired woman?’

Then one day he stopped asking. Only bought newspapers and cut pieces out of them.

Ghost Baby

It was eight a.m.

Vidisha was at the front door, a beaming smile on her face and a loaded tray in her hands.

‘Goan breakfast, just like my mother used to make. I have kailoreo, bolinha, and kangaanchi usli,’ she said, pointing to the dishes. ‘Let me in.’ Then using her elbows, she opened the door and edged past Darya.

‘You're up early,’ Darya grumbled, closing the doors behind her.

‘How come your windows are shut? Nobody does that on Heliconia Lane. It's the safest street in—’

‘Goa. Yes, so I've been told,’ she said and loosened the strings of her housecoat to let some air in. It was humid and Darya had a headache. She'd woken up earlier in the morning to have her coffee but had gone back to bed again. There was a lot of time to kill, and what a glorious feeling it was, to kill it with sleep.

‘You don't look too well still,’ Vidisha said. ‘Poor thing, maybe some good food will help?’ She looked around for a place to sit. Spotted the divan. ‘Ugh, Uncle Pari never took care of this place. We hated coming here after... you know... and then did not come at all. Time has stopped here. I don't think he ever bought anything new after 1989.’ She traced a line of dust on the divan, wiped it, and sat down. Placing the tray by her side, she said, ‘Come, Darya, I made these myself. Taste and tell me what you think.’

‘Shouldn't have taken the trouble,’ Darya mumbled, walking to her. She wondered for a moment if she should mention the peeping, balaclava-wearing man to her. It had slipped from her mind yesterday and it might be good for Vidisha to know about him now that she was putting up her house on rent.

But before she could say anything, Vidisha said, ‘Listen, I want to talk to you about something.’

‘Me too.’

‘First me.’

Darya sat next to her. Picking up a spoon, she debated what to eat first.

‘Darya,’ Vidisha said, looking serious, ‘I wanted to talk to you about Mama and Papa's death.’

Darya straightened her back. Looked at her companion.

Her face was carefully made up, her clothes well-coordinated, and she'd cooked delicacies as an accompaniment for the chat. This was no ordinary meeting; a lot of thought had gone into it.

‘What is it, Vidisha?’ Darya asked.

Like an actor preparing to deliver her lines, she cleared her throat and said, ‘I think their death was not an accident.’

Darya glanced at her, surprised but not particularly alarmed. She had anticipated a dramatic opening, but she was going to wait until Vidisha had explained herself fully before reacting.

‘What do you mean?’ Darya asked carefully.

Vidisha tucked a few strands of hair behind her ears.

‘Vidisha, relax,’ Darya said. ‘Tell me what you're thinking.’

‘Well...’ She swallowed. Looked at Darya helplessly.

‘Do you think there was something wrong with the boat?’ Darya asked.

‘No,’ she replied.

‘Or your parents died some other way?’

Vidisha shook her head ‘No, they did drown,’ she said. ‘That's the problem.’

Darya said impatiently, ‘What is?’

She spoke softly. ‘The police think it's a simple case of drowning. They found alcohol in their bloodstream and the boat was drifting some distance away, close to the shore.’ Her face twisted in a painful grimace. ‘The police said Papa must have lost control in his drunk state. Irene, the boat was called... do you remember?’

Darya nodded but it did not ring a bell. She did recall what the boat looked like though.

To her surprise, Vidisha covered her face. Her body started to shake. ‘Who in their fifties would do something stupid like that?’ she said, her voice thick as if crying. ‘You think they did not know the risks involved? My parents, who were always giving advice... God-fearing... careful with everything and all.’

‘Vidisha, stop,’ Darya said gently. ‘Wait, I'll get some water.’ She went to the kitchen and brought back a bottle of Bisleri.

After a gulp, Vidisha said, ‘I think they were murdered.’

Darya stared at her. After a minute, she managed, ‘Ah, come on,’ but for some reason, not with the forcefulness she wanted.

‘It's true.’ Vidisha held the bottle in a savage grip.

‘The police would have found something if that were true,’ Darya said.

‘The police think my parents were stupid people,’ she said angrily.

‘And what do you think?’ Darya asked.

‘I think...’ She gulped. Then blinked as if wondering whether or not to say the next few words.

‘Well?’ Darya prompted.

‘I think... I think Gaurav had something to do with it.’

Darya choked on a piece of bolinha.

‘What?’

Vidisha spoke in a rush then, eager to get everything out at once.

‘He was living with them that weekend,’ she said. ‘Not difficult at all to get them drunk and I don't know... capsize the boat and all.’

Darya gaped at her. ‘Vidisha, do you even know what you're saying?’

Her eyes grew large and tearful again. ‘I know what it sounds like. He is my brother and all, and how can I go accusing him? But he is a druggie. He needed money all the time. My father was refusing to bail him out anymore. Gaurav called me for money too. Some gangsters were harassing him, he said. Long sob story. But I refused. Then he asked our parents. They refused too. Then he must have decided.’

‘What? To kill them?’ Darya tried to laugh, but something distorted came out.

‘You don't believe me?’ Vidisha said tearfully.

‘Did he inherit any money after their deaths?’ Darya asked.

Vidisha nodded. ‘My parents hadn't made a will. So, both he and I got the house and the money equally. But we don't speak anymore, and he has not been responding to my calls. Must be hiding from the police doing one of his gang things.’

‘Did he come to the funeral?’ Darya asked.

‘Yes, but we had a bitter fight at the end of it.’

A load of shit this is. She only wants to get her brother in trouble.

‘But it has been a whole year. If he was responsible for the death of your parents, why hasn't he taken any money yet, if that's why... if that's why he... killed them?’ Darya asked.

Vidisha's fingers played with the forgotten bowls of food. Her voice was low when she said, ‘Papa had given him some money before he died. Then he stole some money from the house on the day of the funeral.’ She clenched her fists. ‘Just imagine. Such an evil, greedy pig. He'll come back for more, I'm sure of it. Papa had called me up the day before the accident. He said Gaurav was throwing things and getting angry. He asked Gaurav to leave the house. And then...’ she looked up at Darya, her lips trembling. ‘This happened.’

Darya shook her head, yet unconvinced. ‘Vidisha, he's your brother. They were his parents too. Why would he do something like this? Think.’

‘He was involved somehow,’ she said, stubbornly. ‘I know it.’

As Darya searched in her mind for something to say, she heard a sound in the distance. She turned to see if Vidisha had heard it too. She had.

The wail of a siren. Far-off, then closer, then on the street.

Puzzled, they stared at each other. Then jumped up from the divan, cau

sing the bowls on it to rattle.

Darya opened the front door to let Vidisha out, following her outside.

A yellow ambulance was parked at the end of the street, its red and blue strobe light flashing. The noise on the quiet lane was deafening.

Two orderlies pulled out a stretcher from the back of the vehicle, walked across the garden, to the front door of Primavera. A woman was standing there, leaning to one side, looking barely conscious.

‘Zabel Aunty!’ Darya and Vidisha breathed in together.

Even from a distance, they saw the damage: bruises on her arms, a big one across her chest, a purple contusion under her left eye. The right sleeve of her maroon dress was torn. Her grey hair was loose on her shoulders. She rocked unsteadily on her feet.

The orderlies helped her onto the stretcher and walked back to the ambulance. Filip locked the door behind him and followed in wobbly steps.

He stayed with her until she had been strapped in. They held hands. He said something to her. After a few minutes, the orderlies prodded him to step back and closed the doors. Then drove away as Filip watched, his shoulders slumped.

‘Uncle,’ Vidisha cried, running to him. ‘What happened?’

Darya followed in quick steps.

‘What are you doing here?’ he asked dully, not seeming to recognize her at first. Then realizing who it was, ‘Nothing. A small accident,’ he murmured. ‘Nothing to worry about.’ The last word a miserable choke.

‘But you're hurt,’ she said, pointing to the rapidly swelling bruises on his arms. ‘You should go to the hospital too. What happened?’

‘What happened, Uncle?’ Darya asked gently.

The last vestiges of his self-control gave way then. His face crumpled.

‘She had a breakdown,’ he wept. ‘After such a long time. She was doing so well.’

‘A breakdown?’ Vidisha said.

‘The same old... hallucinations... screaming... she hit me...’ he said. A dry cough rattled his chest. He stopped to take a breath. His left eye had swollen up and there were angry welts on both his cheeks. His hands were trembling. He held them stiffly by his sides to steady them.

‘Was it because of Xavier again?’ Vidisha whispered, placing a sympathetic hand on his shoulder.

He nodded but didn't speak. Sniffing, he took out his glasses. Wiped them on his shirt. Put them on.

‘But how did you get hurt?’ Darya asked. She pointed to his face. ‘And all that?’

‘Your aunty got violent. She scratched me,’ he said, taking a hand up to feel the welts, wincing when they stung.

‘Which hospital did they take her to?’ Vidisha asked.

‘Holy Family,’ he replied. ‘Don't take the trouble of visiting her. She should be back in a day or two.’

‘You also need to go to the hospital, Uncle,’ Darya said. She was concerned. He didn't look good at all.

‘No need,’ he mumbled and gently brushed away Vidisha's hand from his shoulder. ‘The doctor treating her is a family friend. Anyway, who'll take care of the house if I am gone?’

‘What's there to take care of? We are here,’ Darya said. Immediately, her mind went to the man from yesterday and wondered if Filip was afraid of something like that happening.

But Filip had already started walking towards his house.

‘But what triggered it this time, Uncle?’ Vidisha asked, running behind him before Darya could stop her. ‘She has been taking medicines also.’

‘Our son... that dead boy... what else?’ he mumbled, hobbling awkwardly, shaking his head. ‘She saw some old photographs and that was it. Heliconia Lane... Xavier... Anton... bad memories...’

That dead boy. Xavier.

Filip and Zabel’s first child, Xavier, was six weeks old when he died in what was then diagnosed as a crib death. Zabel had been inconsolable. Filip had thought a second child might help solve the problem, and in the year that followed Anton was born. But if anything, it only made things worse. Zabel withdrew from her new-born son and fell into depression. She started having panic attacks, episodes of violent rage and hallucinations, and frequently addressed Anton as Xavier, though not quite transferring the vigour of her earlier love to the new boy. In the end, heeding everyone's advice, Filip took her to a doctor who put her on a combination of therapy and medication, but that turned to years of intractable pill addiction.

Anton was five years old when Zabel said his name for the first time and gathered him in her arms. As far as Darya knew, Anton had considered Farideh more of a mother than his own, a sentiment shared, in some degree or other, by the rest of the children on the street.

Darya had been witness to Zabel’s breakdown once, a year after her aunt's disappearance. She had woken up one morning to a commotion outside the house. The residents of the street had gathered in the Primavera garden, trying to pull back Zabel as she deliriously dug into the flower beds. She claimed Xavier had appeared in her dream and told her that Farideh was buried underneath.

The group around her was sceptical at this pronouncement but not dismissive. They dug for half an hour but found nothing apart from a few dead worms, dried leaves, and a discarded slipper.

But the disappointment of that failed expedition was palpable. Paritosh barely spoke or ate for the next few days.

‘But, Uncle...’ Vidisha called out to the retreating figure.

‘Vidisha, let it go,’ Darya hissed. ‘We'll come by tomorrow.’

Reluctantly, she agreed, and they turned to walk back.

‘Well, well, well,’ Vidisha said dramatically. ‘Xavier shows up again. The ghost baby.’

Darya did not respond. Her mind was preoccupied. Returning to Heliconia Lane had brought back many unpleasant memories. As if her life did not already have enough problems.

Unaware of her companions rising gloom, Vidisha continued, ‘Aunty has always been weird about him. She's so attached to him... her dead son instead of the one she should be attached to... her living, breathing son.’

Darya did not remember Anton being particularly affected by his mother's emotional aloofness, probably because Farideh had always been around. But she did remember Vidisha taking up cudgels for him all the time, protesting against one imagined issue or another. Jhandewali, Darya's mother used to call her, a revolutionary.

Now she looked at Darya and remarked, ‘Are you still sick, or what?’ and before Darya could reply, ‘Okay, I am off to meet my new lodger in Panjim.’

‘Yeah, sure,’ Darya said. ‘Your plates and bowls are in my place, though. Don't you want to take them?’

‘They're disposable. Keep or throw them. Your wish. You might need them if you're staying for a few days.’

‘But...’

‘Offo, let it be. Okay, have to run. Have to meet the new occupant of Constellation. He's moving in tomorrow. I'll introduce the both of you, am sure you'll hit it off. Okay bye!’ She waved at Darya and sprinted away.

Darya sighed. Abrupt as hell. Vidisha really hadn't changed that much, her moods were whimsical as ever.

Darya dialled her father.

‘Pa,’ she said.

‘Hello, D. How's it going there?’

He seemed unusually cheerful. Darya wondered whether it was an indication that he had recovered from his surgery or an act to infuse some joy into her thankless job.

‘Pa, this is madness,’ she grumbled.

‘What is?’ he asked gently.

‘Uncle Pari s house is a mess, but you probably knew that,’ she said.

‘How bad is it?’

‘MESS,’ she said, emphasizing each letter.

‘Hmmm,’ her father said in response.

‘I found only one photo album. I thought you said there were several. I don't know where they are now. There are loads of newspaper cut-outs about Aunt Farideh. Of course, you knew that too. I am discarding the clothes, nothing expensive there. I will ship the antiques back home in a day or two.’

‘Any important papers or documents?’ her

father asked. ‘I have a rough idea of what's in there, but last time I didn't have enough time to go through everything.’

‘One sec, let me give you a list of what I thought was important.’

Darya had walked back to Sea Swept. She pushed the door open, her phone pressed between her ear and shoulder. Then stepping into her uncle's room, she picked up a sheet of paper from under the pillow. She'd made the list last night.

‘Here goes,’ she said. ‘Six newspapers from 1989, three from 1990, eight newspaper cut-outs from 1991—all with articles about Aunt Farideh or hoping they were articles about her... you know what I mean. There's another bunch from 1993 but I don't know what they are for. Maybe just useful scrap. The photo album I was talking about. Seven books—five of them on fish studies and two on Indian history. A brochure on gardening tools. A few film song cassettes.’

‘That's it?’ her father sounded surprised. ‘What about the deeds of the house, or a will or a birth certificate? I'm sure there's more. Have you checked everything?’

‘I did,’ she muttered. ‘There's not much to check. Not many tables or drawers unless there's a hidden room.’

‘Don't be silly, Darya, this is serious,’ her father scolded.

‘Tell me what to do then?’ she asked. ‘There really is nothing of value here.’

‘Look again. Get every piece of paper back.’

‘This is it,’ Darya said, sighing. Then softly, she suggested, ‘Could they have been stolen?’

‘The papers?’

‘Yes.’

‘Whatever for?’ her father asked, sounding confused.

‘I don't know,’ Darya said.

‘How?

‘What do you mean, how?’ Darya asked.

‘How could they have been stolen?’ her father asked.

‘Nobody lives here anymore,’ she explained. ‘An empty house is an obvious target for thieves.’

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3