- Home

- Smita Bhattacharya

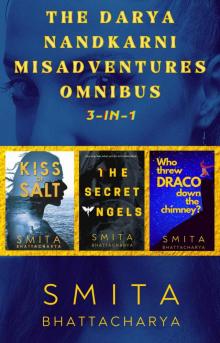

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3 Page 5

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3 Read online

Page 5

‘So good to see you,’ Vidisha gushed. ‘I haven't seen you in so, so long.’

Darya extracted herself with some difficulty and said, ‘I'm sorry about Uncle and Aunty.’

Pain passed over her face like a spasm. Her shoulders fell.

‘That was bad, unexpected,’ Vidisha murmured. ‘The way they were, keeping themselves healthy and all, walking, boating, taking all those health trips. I thought they would live longer than us even.’

‘It was unexpected,’ Darya murmured.

‘Yes,’ Vidisha replied.

They stood in silence.

Then, ‘It's hot. Do you want to come in?’ Vidisha asked, pointing towards Constellation.

‘Well, I did want to see what the decorator has done with it,’ Darya said.

‘You can see it now. Before the lodger comes.’

‘You found one already?’ Darya asked, surprised.

‘Ya, we got a good one, and how long to keep a place like this sitting idle?’ Vidisha said.

‘I'm surprised Filip agreed to it.’

Vidisha gave a twisted smile. ‘He's not the man you knew... Gone soft with age... and they miss Anton.’

‘What’s he up to these days?’ Darya asked. ‘Been so out of touch.’

She shrugged. Then turned to lead the way through the garden. ‘We've all been out of touch. Are you married?’

Darya shook her head.

‘Boyfriend?’

‘Just got out of a very bad relationship,’ Darya muttered.

‘Bad?’ Vidisha prompted.

‘No questions, not as yet,’ Darya said, wearily.

‘Okaaay.’ Vidisha raised her arms in surrender.

‘How are the kids and the husband?’ Darya asked, perfunctorily.

‘All good,’ she replied and opened the door.

Darya was taken aback by what she saw. The second time that day.

‘Amazing,’ she murmured. She remembered little from when the Salgaonkars lived there but was sure it was not close to the carefully curated opulence she was seeing now. Miss Pantsuit had done a good job. ‘This is pretty cool,’ she said, her eyes sweeping over the rich tapestries on the walls.

‘The place was crumbling after Mama and Papa died. I did not want to come here... too many memories. Gaurav was... well...’ Her gaze dropped. She bit her lower lip. ‘So, I gave Bobby a free rein. Do what you want, I told her. You've met her, na?’

Darya gave a slight nod. ‘Interesting woman.’

‘Ya. She has done work for a lot of large hotels. You'll see her a couple more times. I hired her on somebody's reference. I was sceptical at first but look at what a great job she's done. Filip Uncle was also very impressed. If only the umm...’ A thought seemed to strike her then, and she stopped midway. ‘Wait, I have something to show you.’

She walked over to a corner cabinet and took something out from inside the top drawer.

‘I found this when I came to box my parents' things. It was lying on the table, along with that cursed...’ She gave a shudder, ‘...bottle of wine and glasses. It was slightly crumpled, but I straightened it out. Papa and Mama must have taken it out to remember the old days. I'll put it back in the frame. It's a nice picture,’ she said.

Darya only dimly registered what she was saying.

‘Residents of Heliconia Lane,’ she breathed as Vidisha handed over the photograph. It was sepia-toned, in good condition except for some corner crease and a grubby thumbprint or two.

‘See, there is Aunt Farideh.’

Vidisha placed a finger on the thin, beautiful woman standing to the far right. She was wearing a low-cut, floor-length dark taffeta dress, her hands clasped in front of her, a gentle smile on her lips. Her husband stood next to her, proud and upright, one arm resting lightly on her shoulder, the other folded behind.

Like a soldier and his bride.

Darya turned the picture around for a date:

15 May 1989

Ah, my Beloved, fill the Cup that clears

TO-DAY of past Regrets and future Fears—

To-morrow?—Why, To-morrow I may be

Myself with Yesterday's Sev'n Thousand Years

‘It was a long, long time ago,’ Vidisha whispered. ‘A long, long time ago...’ Darya noted how Vidisha's childhood habit of repeating words to stress a point had not left her. They used to make fun of it when they were kids. They used to make fun of a lot of things when they were kids. Vidisha and Anton carried the brunt of it. Mostly.

Darya leaned on the wall, feeling suddenly dizzy. She placed the photograph face-down on a table next to her.

‘What's the matter?’ Vidisha asked worriedly and placed a hand on her shoulder.

‘Vidisha, can we talk sometime in the evening?’ Darya said, her voice weak. ‘I need to go home for a bit.’

‘But, don't you want to eat or drink anything? We have restocked the pantry,’ Vidisha said.

‘I don't feel too good. It's a hot day and I've been out and about... it could be a heatstroke,’ Darya said. ‘How long are you here for?’

‘A day or two,’ she said. ‘Haven't decided. Listen.’ She paused. ‘There's something important I wanted to talk to you about.’

‘What is it?’ Darya mumbled; her stomach queasy.

Vidisha bit her lips. ‘Not now,’ she said and looked around furtively as if afraid they were being watched. It was a gesture so comical that if Darya hadn't been feeling sick, she would've laughed.

Vidisha may have changed how she looked, but she was still the girl Darya remembered: self-important and affected.

‘Okay, later then,’ Darya murmured.

She waved a weak goodbye despite Vidisha's entreaties and staggered back home.

Swallowed By The Night

It wasn't the overbearing heat that had affected her as much as seeing that photograph, taken a week before her aunt disappeared. She knew it because her uncle had gotten only three copies made and having lost his own threw a fit because he couldn't find the negative to make more copies. She remembered her father consoling him over the phone. Seeing the photo again brought back to her mind that unpleasant episode and many more. She and her family had tried to scrape away those memories over the years, but they returned, like the damp patches on the walls of their house every monsoon. You learnt to live with them because you loved the damn house so much.

Like they'd loved Farideh.

Darya did not remember much from the day it had happened. She had been only eight years old and no one had thought she was old enough to be in the know. She recalled the flurry of phone calls, her father rushing off somewhere, probably to the airport, her mother tossing and turning all night next to her while Darya pretended to be asleep. They had told her nothing even after her father returned home from Goa two weeks later. They had filed a complaint at the Panjim police station, but there was little hope.

The police turned Sea Swept upside down to look for clues. They interviewed all those who had been around the house that day, threatening them with dire consequences if they'd seen something and not told them, but even after weeks of intensive searching and questioning, the police failed to find her body. They swabbed the blood they'd found, sealed her clothes in clear plastic bags, and took away most of her things to help with the investigation, but never found her.

And the longer they waited, the more certain they became that she had died. If she had been kidnapped, the kidnapper had killed her; victims almost never survived seventy-two hours after being taken. Or maybe she had fallen into the sea and drowned, and her body would be washed ashore in due time.

Either way, the outcome was dreadful.

Even after he returned, Darya's father continued to follow up on the investigation, calling Paritosh several times in a day and the Panjim police station at least once every other day. Apart from sometimes walking in on him shouting on the phone, Darya learnt little else. Conversations stopped abruptly when she stepped into a room.

She heard th

e story from her mother only much later, when she was thirteen and demanded she be told. Her mother feigned surprise at first, clearly uncomfortable talking about the subject, but Darya insisted.

‘I need to know,’ she said.

‘Let it go. It broke your uncle. We don't want to bring that up again. Kya fayda?’

But Darya asked again and again, and, in the end, her mother complied. She knew it wasn't going to be easy for her mother to speak about it; she and Aunt Farideh had been very close at one point of time.

Her mother started with the story of how Paritosh and Farideh met while studying at the Indira Gandhi National University in New Delhi. Farideh had come as an exchange student to study Indian history and teach Persian. Paritosh was already in his third year at the School of Life Sciences. Either he had had a glimpse of the student-teacher taking the course or simply because he was interested (he never confirmed or denied either), he took up Persian Studies as an elective. It was unusual but not unheard of. The two fell in love over textbooks and timetables and formalized their union one summer in Goa where they had come for a holiday.

There wasn't a lot of objection from anyone; Paritosh, Vikas, and their three sisters were orphans brought up by myriad of relatives who were only too glad that the first among them had gotten married—to an exotic, beautiful foreigner no less. Farideh was estranged from her parents, so she did not bother informing them. They had a Hindu and a Catholic wedding, the latter only so Farideh could wear a white gown—her long-cherished dream.

‘Why didn't she have a Muslim wedding?’ Darya asked.

‘We didn't know how to do it or who to call for it. Anyway, Farideh didn't mind,’ her mother said.

‘How old were they?’

‘Your uncle was twenty-three and she was twenty-one.’

‘She had a degree to teach Persian at twenty-one?’ Darya asked, surprised.

Her mother rolled her eyes. ‘It wasn't so strict in those days,’ she said. ‘Plus, it was an unusual language, one hard to find teachers for, and the university bent some rules.’

‘And how come they settled in Goa?’

‘As good a place as any, that's what Pari said. They had been there for holidays and loved it. Your uncle has a specialization in Ichthyology. He wanted to work with fish. He was different then. Very dashing and smart. Always full of ideas.’

Then another thought came to Darya's mind, one that had bothered her as a child. Her uncle and aunt never visited them when her family lived in Mumbai, at least never together. Darya recalled her aunt had come twice, both times alone and only for a day. It was during their first year of marriage and move to Goa.

She asked her mother about it.

‘Pari wouldn't let her travel on her own,’ her mother said. ‘And he was always too busy to bring her.’

‘One time she had bruises... she'd slipped when getting off the train,’ Darya said, and then wondered if it was a memory she had made up because her mother looked startled. ‘Isn't it?’ Darya asked uncertainly.

Her mother shook her head. ‘It was such a long time ago,’ she said. ‘It's hard to remember. In any case, we realized soon enough that it made more sense for us to go to Goa, especially after they shifted from Panjim.’

The couple moved to Valsolem Beach a year after their marriage. Filip Castelino had been one of Paritosh's regular customers at the fish wholesalers he worked for and he suggested—offhand at first and then seriously—that since their street had space for a third house, Paritosh should consider moving from his rat hole in Panjim to Heliconia Lane. After a brief survey of the empty plot of land by the sea, Paritosh gladly accepted.

Over the next few months, the couple supervised the construction of Sea Swept, scrupulously, lovingly, brick by brick. The Castelinos and the Salgaonkars got together with Paritosh and Farideh like long lost friends, and it would have been hard for anyone to guess, as Darya's mother put it, that they had known each other for only a few months.

‘I was so jealous of their friendship,’ her mother said, ‘I told your father we should move there. So many parties, soirees, endless food, and drinks... a private paradise. I used to die to go there. You loved it too.’

Darya remembered the partying and also her father’s concern over his brother's excessive drinking... tearful late-night phone calls from her aunt... frantic whisperings between her parents... but... were those her imaginations again?

‘It wasn't so bad,’ her mother scolded. ‘Don't talk about your uncle that way.’

‘Aunt Farideh used to drink too,’ Darya remembered. Women drinking at that time was an absolute no-no, but Farideh's follies were quickly forgotten and forgiven.

‘Young couples... an isolated beach... what else is there to do?’ her mother said.

That wasn't entirely true. There were things to do.

About a kilometre down from Valsolem towards Quepem there used to be a popular shack called Evolucion that lasted until the early 90s. After the incident with Farideh, visits soared for a while, probably out of curiosity, then petered down, until it fell unsustainably low and the place shut down.

‘No one should ever trust a place with a misspelling,’ Darya's mother scoffed. ‘They should've known right away something would go wrong.’

‘Ma, the story, please!’ Darya said exasperatedly.

It was Farideh's birthday. Paritosh asked her what she wanted. A grand celebration, she told him... a party at Evolucion. The usual practice was for them to have a house party, but Farideh wanted to do something unique, something everybody would remember for days to come.

Paritosh complied. He booked a fifteen-seat table at a private corner of the shack and invited the residents of Heliconia Lane along with a few others from his shop to join in.

The housemaids were paid overtime to mind the children. Paritosh left early to take care of the arrangements. The Castelinos and Salgaonkars arrived at nine thirty, the rest came in at ten.

They waited an hour for Farideh to turn up, joking about how long it took for women to get dressed and why Farideh needed to wear makeup at all; she was so beautiful. By the time it was ten thirty, everyone was already quite drunk when a worried Paritosh decided to check in on her. Maybe he had said something to upset her and she hadn't shown up out of spite. She wasn't that way usually, but then...

He left the group and walked briskly towards Sea Swept. The sea was particularly tumultuous that day and walking along the beach was less than easy. His clothes flapped in the wind as he scrambled over dunes and prickly bushes.

He didn't find her, of course. What he found instead were the parts of her that were left behind. A glittering red shoe, its heel wedged between the stones near the front gate, the second shoe was found a day later on the shore; scuff marks on the floor, starting from the master bedroom through the veranda and to the garden as if there had been a struggle and she was dragged; patches of water and sand on the floor; trampled grass outside.

The master bedroom had been turned upside down. Jewellery lay scattered on the dressing table, the expensive ones gone. The thirty lakhs rupees Paritosh had hidden in the cupboard had disappeared. A chair with a broken leg was toppled over. Scattered clothes and books. The red strapless dress Farideh had been planning to wear that night was aflame in a plastic water drum outside.

There were no signs of forced entry. So Farideh either knew her kidnapper or had been careless to leave the front door open. In Heliconia Lane, they often did that.

His friends arrived a few minutes later and agreed with a stunned Paritosh: something had happened to Farideh. The little boy Anton, then only eight years old, was especially inconsolable. He claimed to have seen Farideh from the window of his bedroom, being pushed inside a black or dark green ambassador car by a tall man. The boy was crying so hard he fell down, hit his head, and had to be rushed to the Goa Medical Hospital. His claim was later corroborated by hawkers on the street a kilometre away who had seen a vehicle matching the description speeding along the road

around the same time. No one recalled seeing a woman inside, but the car had whizzed past them too fast.

After this, the police concluded the kidnapper had come from the main road and not the beach as they had earlier suspected. Paritosh insisted the police widen their search, question everyone who was at the shack that night, look for suspicious vehicles, put out flyers asking for information, but the police chastised him for overreacting, advising him not to teach them their jobs.

The search for a black or green ambassador was stepped up and the car was found a few days later, abandoned near the Madgao railway station. The insides had been cleaned with bleach. The driver (or thief) was never found.

The police tried to look for other clues, but it had already been a month since the disappearance. Paritosh put in a few desperate calls for information of his own in newspapers. Filip tried to pull as many strings as he could, but it was all to no avail. This was 1989, a time when the media did not hurry along investigations, and police inquiries relied more on old-fashioned legwork and a network of informants rather than the Internet and sophisticated forensics.

Once or twice though, a clue cropped up to give hope.

Two months after her disappearance, a junior constable taking pity on Paritosh, who visited the police station every day, told him that a hippie named Andy—a part-time bartender at Evolucion—claimed he had seen Farideh that night on the beach. She appeared to be running from a man giving her a chase. Andy hadn't come forward earlier because he was wary of the police and also ashamed, he had done nothing to help when it had happened.

The police hadn't believed him. He had been stoned when he showed up at the station, as he must have been on the day he claimed to have seen Farideh. Paritosh tried to locate the man but was told he had left for his home in Russia.

That one year, Darya's family visited Sea Swept a little more frequently than usual, to be around her uncle as he struggled with his loss.

‘Your chacha became someone else,’ her mother said. ‘We saw less and less of him. He kept the bedroom as it was. Locked it when he went away. He allowed no one to touch anything in it. He still had hope, you see. But we knew she was gone. The police told us she was dead. So many women kidnapped and raped every year; the men who take them always kill them so as to leave no evidence.’

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3

The Darya Nandkarni Misadventures Omnibus: Books 1-3